On June 28, 2009, democratically elected Honduran President Manuel Zelaya was ousted by a military coup. In response to Zelaya’s push for a poll to gauge public interest in constitutional changes, the Honduran Supreme Court ordered the military to arrest him. He was then sent to Costa Rica in his pajamas.

The coup led to nearly 13 years of right-wing rule, marked by collusion with drug trafficking organizations, widespread privatization, violence, repression, and a significant migrant exodus. During this period, the Honduran left organized a strong resistance movement. In 2022, Xiomara Castro, Zelaya’s wife and a leader of the anti-coup resistance, was elected president, signaling a major shift in the country’s history.

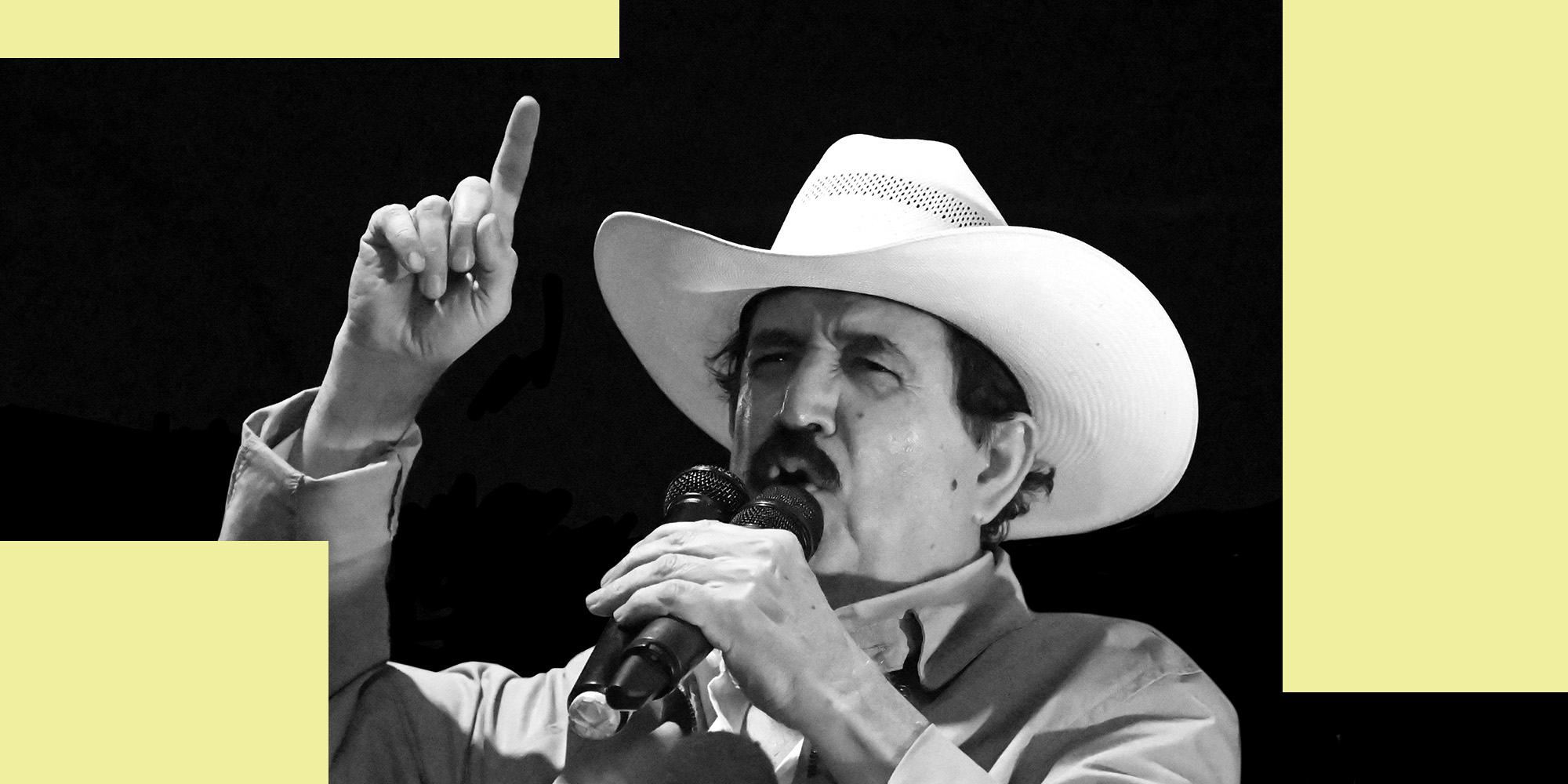

In this episode of Deconstructed, Zelaya sits down for an exclusive interview with journalist José Olivares to discuss the 15th anniversary of the coup, the ensuing resistance movement, the right-wing and drug trafficking organizations’ control, and the U.S. government’s role and influence. Host Ryan Grim and Olivares delve into Zelaya’s interview, recent developments in Honduran history, and present the full Spanish-language interview with Zelaya.

Deconstructed is a production of Drop Site News. This program was brought to you by a grant from The Intercept.

Transcript

Ryan Grim: Welcome back to Deconstructed.

I’m Ryan Grim and, as I mentioned in the last two podcast episodes, Jeremy Scahill and I have left The Intercept, and have launched a new independent news organization with some support from The Intercept called dropsitenews.com.

I’m joined today by former Deconstructed producer José Olivares, who is now working with us over at Drop Site News. He’s going to be talking to me today about a fascinating interview that he was able to land down in Honduras with the former Honduran president, Manuel Zelaya — Who, as some of you may recall, was ousted In a 2009 military coup, with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton at the time immediately recognizing the new military government, or at least recognizing the pathway to keep that military government in power until there were new elections put into place. It is often referred to — and, I think, accurately — as a U.S.-backed coup, though it is still quite murky how much involvement the U.S. itself directly had, and whether it was purely driven by the right-wing in Honduras, which then took power for the next 12 years.

Since then, Zelaya’s wife Xiomara Castro has come back to power on a democratic socialist platform, bringing Zelaya kind of back into the presidential fold. The left in Honduras is still surging and is likely to maintain the presidency in the next election.

Recently in Honduras there was a celebration of the reconquest of power by the left in Honduras 15 years after the coup; it was a ceremony to mark the 15th anniversary of that coup. José Olivares was in Honduras for it, and there he was able to interview former president Zelaya.

So, José, thank you so much for joining us to talk about this interview, and we’re going to play a whole bunch of clips from it.

José Olivares: Awesome, thanks for having me.

RG: So, José, tell us a little bit about this celebration. Why was it held, and who was there?

JO: Right. So, the celebration was held in Tegucigalpa, which is the capital of Honduras, and it was commemorating the 15-year anniversary of the 2009 coup. There were government officials from Cuba, from Venezuela, from Mexico, as well as social activists, trade union activists, trade union leaders, activist leaders from around Latin America, as well from Argentina to Mexico, all over Honduras. And it was organized by the party, by Libre, it was a select social event, but the event really was commemorating the 15-year anniversary of the coup — and not just the anniversary of the coup, but also the years of struggle that the Honduran people were engaged in, in response to the right-wing kind of reaction that came out of the 2009 coup.

I think what’s important to recognize here is that during these 13 years that the right wing was in power, they were fully supported by the U.S. government. There was a lot of repression, a lot of reaction that came from the government. There were killings of activists and land defenders throughout the country. Also, a lot of right-wing neoliberal policies that were put in place. Essentially, the country was sold off; I think, about a year after the coup happened, they even had an event that essentially was saying, hey, all these international companies, come on in, Honduras is for sale. [It] really ended up putting a lot of secretive policies in place, a lot of right-wing privatization policies in place, in tandem with the reaction, with the repression against the activists and the resistance movement.

So, this event, this 15-year anniversary was a really, really fascinating event. I mean, you could really feel the energy when you were walking through the halls of the hotels where the events were held, and even at the event itself, which was commemorated in the space where the resistance movement was organized — you know, the same day that President Zelaya was taken to Costa Rica by the Honduran military. That space, that event, the energy was electric. There were people chanting and yelling, chanting and saying, “they’re never going to return, these coup-plotters, these right-wing coup-plotters, they’re never going to return,” and really just kind of recognizing the sacrifices that the Honduran left was engaged in during these 13 years of struggle before Xiomara Castro was elected in 2021.

RG: Before we get into some more of the interview, he talks to you about the way that narcotraffickers effectively took over significant parts of the state. And so, from an American perspective, I see at least two obvious ways that what the U.S. has been doing to support the kind of right-wing elements of Honduras have directly blown back to the United States. One of them is, of course, with the rise of narcotrafficking there, and then the other is the complete collapse of the Honduran economy, which resulted in surges of migrants streaming north, from Honduras through Mexico, then down to the southern border, and further then kind of polarizing and radicalizing our own politics around immigration.

What was the overall posture that the people there had towards either Democrats, or Republicans, or the U S. government? Do they feel like they have anybody that they can potentially work with? Or do they see themselves in a straight up adversarial situation with the U.S. administration, no matter who’s in power?

JO: I think, publicly, the Libre party very much express that they’re willing to work with the U.S. government. And still, to this day, there still are some links that were established from these 13 years of the right-wing governments with the U.S. government that still continue to this day.

You know, Xiomara Castro has only been in power for two years now, and a lot of what members of Libra say, they say, a lot of these right-wing policies, right-wing links, we’re not able to get rid of them as easily, especially [with] 13 years of right-wing policies and this relationship with the U.S. government. We’re not able to do away with them, just in two years.

And the relationship with the U.S. really does go back for decades, over a century. In the late 1800s, the U.S. government started getting involved in mining, and then, in the 20th century, the U.S. government was getting involved in banana farming and agriculture, and that’s where the term “Banana Republic” comes from, right? That’s what Honduras was called, because, essentially, Honduras was the staging ground, the U.S. government’s main location for their influence in Central America.

After World War II, when the U.S. government is really railing against the threat of communism spreading throughout Latin America, Honduras was the main place, the main location where right-wing paramilitaries were trained, where right wing armies were trained, in order to combat these revolutionary movements, or to fight alongside in these civil wars, to try to root out any sort of leftist opposition that was spreading in Central America.

Honduras was so much of a place where the U.S. government could really just go in and rely on it. Some government officials back in the day even called it “U.S.S. Honduras,” right? It was essentially what they called the country.

So, there’s a long history of the U.S. government being involved in Honduras’ internal affairs. Even though Honduras never really had a revolutionary movement or a civil war, in the 80s there was a dirty war. There was a lot of repression, a lot of funding from the U.S. government, and a lot of repression against left-wing activists, trade unionists, etc., that were either disappeared or killed by the armed forces that were trained by the U.S. government.

So, now we’re looking at the 21st century and, in an interview, you’ll hear Zelaya essentially say, the Democrats and the Republicans, they’re essentially both the same, right? They both serve the same imperialist interests for the transactional companies, just looking out for their own interests. And so, to us, it doesn’t really matter who is in office, whether it’s a Republican president or a Democratic president. Essentially, they both are looking out for U.S. corporate interests and transnational company interests, so they’re going to do whatever they want in order to maintain that power and maintain that hold.

He makes an appeal to the working class in the U.S., essentially, saying, it’s up to you. It’s up to the working class in the U.S. to really put up a struggle and put up a fight against these pro-capitalist, pro-corporates politicians.

RG: I noticed he did say that the one exception to that would be, he’d actually be happy if Bernie Sanders or Noam Chomsky were elected president of the United States. Not much risk of that happening anytime soon, so I think his answer probably stands.

But there’s also an interesting phenomenon that Central and South America have a significant Palestinian population. And so, you asked Manuel Zelaya what the progressive Honduran government’s posture toward the ongoing slaughter in Gaza was, and what did you make of his answer?

And what we’re going to do here, by the way, because the interview was conducted in Spanish, we will post a full English language translation of the interview over at The Intercept, and also over at Drop Site. We’ll go through the questions and answers here. You can highlight some of the most interesting parts of at the end. For listeners who do speak Spanish, we’ll play the entire thing so you can hear Zelaya. It’s a rare interview, and I think it’s a fascinating one, but if you want the English language version, you can pop over to either one of those websites to get it.

So, what did he have to say about the war in Gaza?

JO: I can read some excerpts from his answer. When I asked him about the his perspectives on Palestine, essentially, he condemned the genocide, and he said, “We consider, and Xiomara,” who is his wife, and the current president of Honduras herself, “And Xiomara herself has said that, in international forums, that this is a truly unprecedented fact that in the 21st century, it is incredible that, in the eyes of the world, without respecting international law, by violating all treaties and all concepts about peace and coexistence between nations, and about respecting the United Nations’ resolutions, Israel carries out a ground invasion with tanks, with bombs, with the effects of violence on the civilian population of Palestine. Because when an army fights an army, that is a war. But this is not a war, this is a genocide, because of the extreme brutal response from Israel that is exceeding all limits, even those of the laws of war.”

And then he goes on and continues, and says, “The first condemnation that the Xiomara Castro government made was against the bombing that affected Israel, which caused deaths within Israel. People were killed within Israel.” He’s talking, of course, about the October 7 attacks. That was condemned. That was the government’s first action. “But then the terrible response from Israel is one that totally exceeds any limits and has the world outraged. Do you know who has lost a lot of prestige? The United Nations Security Council. I mean, you see the Security Council of the United Nations, it’s remained simply a rhetorical representation of the interests of the powerful. They’ve not been able to stop this aggression, they’ve not been able to achieve a permanent ceasefire. They have not been able to recognize the two states — the Palestinian and Israeli states — which was one of our main positions.”

And then he goes on to say, “To solve this problem, because the problem must be solved, we cannot live under the crushing boot of fascism which, in this case, is being imposed on the Palestinian people.”

RG: And so, how big a topic was Palestine at the conference?

JO: It was quite big. Most government officials who got up and gave speeches were speaking about it, were denouncing the genocide. There were people walking around wearing keffiyehs. And then, if you exited, and went around to the downtown area and kind of walked around the town a little bit — which we were able to kind of see a little bit — you did see graffiti and spray-painting along the walls, essentially calling for a ceasefire, calling for Israel to stop the genocide.

During this whole process, because of the political context that a lot of Latin America finds itself in, some of the more left-wing officials that were there were also pointing the finger at the U.S. government, at the Biden administration, for arming Israel and for perpetuating the genocide.

So, even though it wasn’t the central question there, obviously it was very much present there during a lot of these conversations and a lot of speeches that were being given at this event.

RG: You mentioned at the top that he said that, in general, Honduran government doesn’t see much difference between Republicans, Democrats. But you asked him about the upcoming election and politics in the United States, and I thought his answer was interesting. It’s interesting to hear how a kind of leftist leader in Central America views our two-party system. Do you mind reading a little bit of that?

JO: Of course. So, he says, “We have no preference in these elections between the Republican Party and the Democratic Party. We believe that, in the end, they act the same. They act in the interest of Wall Street, the military industrial complex, the interest of a global elite that, through capitalism, has already taken over all the assets of wealth: the rivers, the seas, the forests, oil. The world elite manages it all through their speculative financial system. The planet’s main resources of raw economic goods are those that influence the U.S. government.

“So, in the end, you can vote for a democratic president. We would have preferred — we would have wanted Bernie Sanders to be president, for example, or Noam Chomsky to be president, for example — but the people in the U.S., they organize their own parties, and the parties choose their candidates. So, that’s important to point out.

“And we would like the North American people first to make clear that the U.S. government should not be an aggressor empire against other societies, regardless of who takes office. The North American people should make clear that the U.S. should not have intelligence agencies planning coups or interfere in other countries, and that should be clear. That we must at least respect — and listen carefully — the planet, so that we all have air, to ensure that climate change does not continue to be as aggressive as it is now.”

And then he goes on to say, “What people want is to eat, what people want is to be clothed, to quench their thirst, to have a roof over their heads, and shelter, and warmth. What kind of a crime is that for human beings? And to think that the great powers, once they solve their problems, they forget about the suffering in Africa, in Latin America, and in many countries in Asia, as well.”

Then he goes on to say, “So, we must demand humanity in the face of the world order. And the United States is co-responsible for the current world order. Therefore, we must call on them, the American people, to reflect on that.”

RG: Yeah. So, you can see in that answer, I think, both why the Honduran people elected him president and, also, why he was couped as president. And you asked him about that coup 15 years ago, and he gave a rather, I thought, striking answer that still resonates quite deeply with him.

Why did he get couped out of office? And what had he been able to accomplish before that happened?

JO: So, Zelaya is a really fascinating character in Honduran history, he’s a bit of a contradictory character as well. When he was elected in 2005 — he entered office in 2006 — but he kind of came in and he would campaign on this almost center-right campaign, a very liberal politician. But, once he was in office, he began shifting to the left.

Now, he wasn’t calling for the nationalization of industries or anything like that, but he did raise the minimum wage, he did implement some modest land reform. Extreme poverty, he did kind of reduce a little bit. But what really upset the right-wing in Honduras and the U.S. government was that he joined ALBA, which is the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of our America, which is a trade and intergovernmental organization that was organized and founded by Cuba and by Venezuela. So, the fact that he was growing closer to Cuba and Venezuela and that he was putting forward some modest reforms really started shaking up the political situation in Honduras.

In 2009, we had elections in Honduras — or elections were slated to take place — and in the Honduran constitution, which was written in 1982; again, going back to 1982, this constitution was written partly with the help of the U.S. government. It is a pretty right-wing, pro-military constitution that was written amid this context of military disappearances, killing left-wing activists, etc.

In the lead up to the 2009 elections —presidents were only, at the time, allowed to run, to be in office for one term — the 2009 elections, Zelaya started considering and started listening to calls for establishing a constituent assembly which would rewrite the 1982 constitution, but he began receiving some pushback from the right. So, what he did is, in early/mid-2009, he proposed, let’s have a poll. A poll that would say whether the Honduran people wanted to include a referendum or a new ballot measure in the 2009 fall elections. And then, that ballot measure would be to see if people wanted a constituent assembly to write a new constitution.

So, it was several steps away from actually writing a new constitution. He wouldn’t be the president of Honduras when that new constitution was written but, because he was pushing for this constituent assembly, the U.S. government and the right-wing in Honduras, they accused him of trying to write a new constitution so that he could consolidate his power and stay in office, and be able to be reelected in those 2009 elections, which logistically [just] wasn’t true, right?

RG: Right. It’s hard to see how you could do both of those at once.

JO: Exactly. Exactly. He forcibly tried to push forward the poll for Hondurans to vote to see whether they wanted this ballot measure in the elections later that year. And, on the morning of that poll when that poll was supposed to be introduced, military officers stormed into the presidential palace. They arrested him while he was still in his pajamas, they put him on a plane, and they sent him to Costa Rica while still in his pajamas.

Now, at this time, the U.S. government was slow to denounce the coup, but the Organization of American States, the United Nations, they very much denounced the coup, and said, this is not allowed, Zelaya needs to come back into office. And then, the Obama administration finally said, OK, well, this coup is not right.

But, behind the scenes, they were working with the coup-plotters and the right-wing opposition that organized the coup to make way for the 2009 fall elections, so that the question of Zelaya’s coup would just be moot, right? And this is something that is not just speculated, but this is something that Hillary Clinton — who was Secretary of State at the time — she writes about it in her autobiography, “Hard Choices.” She talks about how they were really trying to make way for those fall 2009 elections so that the coup would just be a moot point. And then they have this veneer of, oh, we’re going back to democracy, we had these elections, we’re good to go.

In 2009, the elections take place, the fall elections take place, and a right-wing president, Porfirio Lobo, was elected. He took office in January 2010, and then the right-wing reaction came.

So, when I asked Zelaya about the coup, he gave almost a bit of an emotional response, right? I mean, it’s been 15 years since the coup but, obviously, it’s very much present, it’s front of mind. He’s asked about it almost everywhere that he goes; not just by journalists, but also by his friends, by his family members.

And then, this is what he said to me, he said, “A coup is violent; well, the way that it was here in Honduras was violent. Because this was not a soft coup, it was a military coup d’état. The human heart hurts so much and bleeds so much that many decades will pass and people will continue to talk about it. For me, logically, my heart breaks talking about the topic, because there’s pain, there’s suffering, there’s tragedy, and I never thought that in the 21st century — and in Honduras, which is a neighboring country to the United States — they could plan an attack to break the country’s institutions.”

Then he goes on to say, “A coup is a war. It is a breaking of a social contract. It is the breaking of the established order for the coup-plotters to prevail. And you see in Honduras who prevailed: the elites that already existed. But they became organized, and it was organized into a mafia. They became gangsters, they destroyed the state’s finances.”

Then he goes on to say, “Those governments enriched themselves. They plundered, they stripped the country of its wealth. That was the result of the coup. Who benefited? The transnational companies, the elites. So now,” and then he goes on to talk about his wife Xiomara Castro’s presidency, “So, now a progressive government has arrived, a democratic socialist government. We have found that the elite is protected by constitutional laws, by free trade agreements, they’re protected by everything. So we have a bourgeois state facing demands from a democratic socialist state. That’s what we have here. That is the result, the disastrous result, of a blow to the heart of the Honduran people. Shameless murderers, reactionaries whose crimes have still gone unpunished.

“Here, the coup-plotters don’t even get a traffic ticket, not even a slap on the wrist. Instead, they’re offered political parties, as if they are a democratic option. It’s so absurd, the Honduran rights, which put the generals in office who carried out the coup, proclaimed themselves to be a democratic alternative. Those who murdered, those who looted, are democratic alternatives. It’s totally absurd.

“But that is what I can tell you in a few words about the tragedy that we experienced, something that Xiomara, with her popularity, with Libre, with the resistance reversed. But the body of the dictatorship continues to be here. It is alive. As they say, ‘The head of the dictatorship may be gone, but his body, with death rattles, is still kicking and shooting.’”

RG: So — and we’ve covered this here before — what policies the right-wing government was able to put into place, and the way that they were kind of able to link them to treaties, particularly with the United States, has left their dead hand still hanging over the new democratic socialist government in Honduras? That, even though it has a mandate from the people, it’s difficult for them to accomplish as much as they would be able to otherwise.

And what’s so remarkable — and people would think we were making this up if they haven’t been following this closely — is that the president that wound up eventually getting into office, he was president of the National Assembly when Lobo was first elected and then became president, Juan Orlando Hernández, is now sitting in federal prison in the United States for his role in narcotrafficking. A role that you asked Zelaya about, because we now know, because the U.S. prosecutors have said so and have admitted publicly, that the United States had knowledge of his role in drug trafficking, going back many, many years.

So, what was your conversation about Juan Orlando Hernández like with Zelaya?

JO: You know, the question of Juan Orlando Hernández is one that continues to kind of linger, and it was very much present there in this event in Honduras. The day before, the day that we were all flying into Honduras for this event, he was sentenced in a New York federal court to 45 years in prison for drug trafficking.

Going back to 2013 when Orlando was elected, he was elected under questionable circumstances. I mean, there were a lot of allegations that that the elections were fraudulent. And then, once he was in office, he continued the far-right policies, the privatization policies, but he continued to consolidate power to an even more extreme degree.

He had his own police force and he engaged in intense repression, but he was also able to consolidate power within the government. He was able to restructure the supreme court and put his own friendly Supreme Court justices in power. And then, what he did, which is a very hypocritical move, in 2016, he was able to change the constitution to allow him to run again.

RG: Isn’t that nice? Gee, I thought that was the whole thing that the U.S. and the Honduran right were so concerned about with Zelaya.

JO: Exactly.

RG: How nice.

JO: How nice, how nice. Yeah.

So, in 2017, he runs again for office, he moves the non-reelection clause from the constitution, and then he wins, right? But these 2017 elections—

RG: And “wins” is in quotes. Right.

JO: They were extremely, extremely difficult. What was interesting is, the day that the election was taking place, the computer systems were showing that the opposition candidates — who were linked to Xiomara Castro and Zelaya — they were in the lead, they were slated to win. But then, mysteriously, the computer system shut down. Then, when the computers come back up, Juan Orlando Hernández is in the lead.

RG: The words that news outlets use for the election is “marred by irregularities.”

JO: Marred by irregularities.

RG: Ah, well, nevertheless.

JO: Nevertheless, reelected.

But what is interesting is that, days after the election, the United States’ State Department, they came out and they said, you know, we respect the elections, we recognize Hernández’s election. He wins. Please stop the demonstrations.

RG: And this was the Trump administration, which was really feeling its oats when it came to boosting the right throughout Latin America.

So, for all the folks who say that, hey, “Trump may be awful but, at least he’s kind of non-interventionist and isolationist around the world,” certainly, that was not the case for the Trump administration in Central and South America, where they did a lot to intervene in the politics of most of those Latin American countries to elevate the right.

JO: Absolutely. And so, after the state department, they say, we respect the elections, we recognize Hernández’s election, years later, when Orlando Hernández is extradited to the U.S. for drug trafficking — this was a couple of years after his brother was convicted of drug trafficking — and then the United States justice department years later say that the 2017 elections were fraudulent.

And, if you’ll excuse me, I’m going to read an excerpt from one of the filings from the Justice Department. This is what the U. S. prosecutors from the Justice Department write in one of their documents, they say: “In 2017 during Juan Orlando’s reelection campaign, Juan Orlando’s drug trafficking coconspirators again provided millions of dollars of drug money to Juan Orlando’s campaign, to ensure that Juan Orlando would remain in power, and their massive cocaine operation would remain protected, just like in 2013, Juan Orlando used that drug money to bribe election officials and manipulate the vote count to fraudulently win the election, including by shutting down the computer system of the agency responsible for counting votes.”

So, this is an election that the U.S. State Department said they respected, that they recognized. And then, years later, the Justice Department comes out and says, no, these elections were fraudulent, Hernández’s win was due to drug trafficking money and corruption.

RG: And not that many years later, we still talk a lot about the open questions about the U.S. government role in drug trafficking in the 1980s, and supporting governments that were linked with drug trafficking, or supporting rebel groups that were linked with drug trafficking. Here we are in 2017, with the U.S. administration basically solidifying an obviously stolen election that puts into power or reelects a narco-president.

So, just to underscore, we’re not talking about ancient times here.

JO: Yeah, this was very, very recent. I mean, 2017. And, obviously, the effects of it are still being felt today in Honduras.

And I asked Zelaya about the 45-year sentence that Orlando Hernández received — you know, he was convicted, and then he was sentenced to 45 years in prison — and I asked him, because I said, you know, in one of these Justice Department documents, prosecutors claim that Juan Orlando Hernández was receiving bribes from organized crime since back in 2005, but the U.S. still continues to support Hernández. And I asked him what the role of the U.S. in Latin America was, with this context. And this is what he answered.

He said, “History always repeats itself if conditions don’t change.” And then he goes on to say, “How did they get here? How did drug trafficking enter? Noriega, for example was a CIA collaborator.”

Noriega was the dictator of Panama, who was a CIA asset. Later, he was trafficking tons and tons and tons of cocaine through Central America. But he says, “Noriega, for example, was a CIA collaborator. And then the United States — after they were Noriega’s main ally — brought in 20,000, 30,000 Marines, helicopters, and they overthrew the government and tried him.”

“Then he goes on to say, “So, who understands them? That’s why I’m telling you, who understands these North American policies? Juan Orlando was their main ally, but not since 2005; according to these investigations by the DEA, the Hernández cartel begins in 2002.” Then he goes on to say, “And there are reports that the DEA itself has published where the drug traffickers say that, and they’ve said this in their statements. I don’t have to believe them. Why believe them? But they’ve clearly stated that they financed my overthrow, and that they gave money to my adversaries to contribute to my overthrow.

“Because they didn’t let me finish my presidency; I had seven months left. And when the national party takes power, they made a statement there in that trial in New York saying, ‘we will never again leave power,’ and they practically swear an oath. So, of course, perhaps what your underlying question is, a cartel was formed. Not just bribes, but they formed a cartel within the state itself. And they remained in power for 12 years and seven months until the people united. They consciously, responsibly, placed Xiomara — a leader who emerges from the resistance — and makes her president.”

Then he goes on to say, “I should say he was convicted, but the sentence downplays his conviction. Because he was convicted for three crimes, and the prosecution asked for the maximum sentence for those crimes, and he was given the minimum sentence for those crimes. For me, I mean, as politicians, we’re not worried about that. Absolutely not at all. Because we believe that justice should be applied in our countries.”

Then he goes on to say something interesting. He says, “As a politician, I’ve said it before, we’re not worried about Juan Orlando being punished. I want them to take more time away from his sentence, so that he can return to Honduras soon, and we can defeat him again in the polls. Because the people no longer want that type of sickly, harsh sectarianism, of dictatorship, of repression, that has subjected Honduras to 12 years and seven months of dictatorship. The people no longer want it, so we’re not worried.”

RG: So, there you have one more moment of the way that the Latin American right, the U.S. government, and drug trafficking, just have gone hand in hand, policy-wise. And then, we wonder later, why do we have this drug problem and why do we have this migration problem? Never once wondering, well, maybe it has something to do with the constant destabilization and allying with narcotraffickers that we’ve done.

Now, obviously, the critics of the left throughout Latin America will say, it’s not just the right that traffics and drugs. And that’s certainly true, and there have certainly been some left-wing organizations, particularly in Colombia, who evolved, basically, into narcotraffickers.

What’s your overall analysis of how the narcotraffickers fit politically into the political economy of Latin America?

JO: That’s an excellent question. And I think we have to recognize that, yes, of course. Especially in Colombia, we see the FARC, right? The Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, right? This left-wing guerrilla movement that kind of began in the ’60s.

When the DEA and when the U.S. government and the Colombian military took out the major cartels in the ’90s in Colombia, there was a vacuum, and the demand for cocaine still was high. And who filled that vacuum? Well, the FARC, and the right-wing paramilitaries, right? And so, it’s an extremely profitable venture, it’s an extremely profitable business, and that’s how the FARC was able to finance a lot of their operations, was through drug trafficking.

But I think what’s important here is that these organized crime groups and cartels, they behave like businesses, right? And so, they’ll work with whichever politician is going to help them, regardless of political party, right? If we see the history of drug trafficking throughout Southern America, Central America, and Mexico, we see how drug traffickers were collaborating with the military, regardless of political party, with federal police, regardless of political party. And, essentially, they act like businesses. They have their own lawyers, their own lobbyists, etc., that are able to kind of work with politicians in order to finance their own operations, and just make as much money as possible, right?

And I think that’s an important context, that’s an important way of thinking about narcotrafficking, is that this is a business, you know? And, like every business within the capitalist system, they’re going to be appealing to certain politicians, it doesn’t matter if they’re right-wing or left-wing, in order to just try to make as much money as possible, as any business would within a capitalist economy.

RG: And, finally, you asked him about what his sense was about the kind of political direction of Latin America. You’ve always got Javier Milei with his upset in Argentina, the eccentric libertarian. But then you have the left holding on to power and maintaining dominance, really, in Mexico, Gustavo Petro in Colombia.

And it led to some flowing, flowery rhetoric, that was actually, I thought, pretty impressive at times. We don’t need to go through the whole thing; he gets into Hegel and Jose Marti, and you can check that out over at either The Intercept or Drop Site, if you want to read that.

But there was a fun part that he ended with that involved Mike Tyson. Was curious if you’d be able to read that.

JO: Yes, of course. He says, “Look, I’ve always placed a lot of trust in people’s common sense. You may have an illiterate person who is unable to read or write, but he will have a greater sense of justice than the most intellectually developed person. He has more of a sense of power. Power is a human instinct. Power is like food. People can be peasants and know what power is for, and how power is used. That is something in a person’s mind. Power, will, justice, and the most sacred thing: freedom.

“But it’s not the freedom of Mike Tyson, and I admire Mike Tyson. It’s not the freedom of a boxer like Mike Tyson, who gets in the ring and challenges you, and you know he’s going to kill you with one punch. That’s not the type of freedom I’m talking about, that we are all equal. We are all equal according to our capabilities and according to our needs. To create fair governments in a better world, that is still possible. We have not lost our faith. And I think that’s what keeps us standing.”

RG: Any final thoughts on President Zelaya? What did you make of him as a person?

JO: Yeah, I thought it was a really interesting interview. I was kind of nervous. You know, he’s, I want to say, maybe six-two and six-six? He’s a very tall, towering figure, with this kind of booming voice, and this very thick mustache. And he walks very slowly, and he has just this presence around him. And maybe it was the context — you know, he was surrounded by his supporters, etc., that was really interesting — but he was kind of a bit of an intimidating figure. But he was very relaxed, very calm. He came in, and he was eating an empanada. I think we had kind of taken him from his lunch when he came in to do this interview — but he did express a lot of hope in the people. In the power of the people. And a lot of hope, obviously, in his wife’s government.

What’s important to mention is that Xiomara Castro’s government is not quite perfect, right? There are still a lot of links and a lot of training from the U.S. government that is flowing into the armed forces in Honduras. And, you know, you ask Hondurans and you ask people within the Libre party, you say, “hey, what about some of these policies? Or what about some of the criticisms?”

There’s a lot of criticism coming from land defenders and from indigenous groups throughout the country, saying that not enough has been done in order to protect them, in order to protect their lands. And you ask members of the Libre party, what do you make of these criticisms? And they say, well, it was 13 years of a narco-dictatorship, is what they say. We’re not going to solve the damage that was done within those 13 years in only two years of Xiomara Castro being in office, right?

There are elections coming up next year, so we’ll see how those go.

RG: And she’s back to not being able to run. How did that happen?

JO: That’s a good question, that’s a good question. We’ll have to ask the Juan Orlando Supreme Court about that.

RG: Term limits for the left, but not for the right, is the basic policy, it seems like.

JO: Exactly, that’s exactly it. What’s interesting is that her government, they have put forward also some modest reforms. You know, they’re not nationalizing industries or nationalizing land or anything like that, they’re putting forward some modest reforms.

But what’s interesting to see is that — and they highlight highlighted this during the 15-years commemorative event — a lot of members of her cabinet were activists, and they’re very young people who were active during the resistance movement after the 2009 coup. And they put up this video where it shows young student leaders and activists getting beaten by the police. And then, right next to it, they show an image of that same student leader, who is now the secretary of immigration, for example, or different cabinet positions.

So, it’s really interesting. It’s a very young government, who are literally young. I mean, they’re very young people who are in the cabinet. And I think they’re still trying to get their bearings and figure out what to do after 13 years of this right-wing reactionary period.

RG: All right. Well, thank you so much for that, Jose. I wish I could have been there, but glad that you could make it, and thanks for doing this for us.

JO: Yeah, thanks so much, Ryan. And next time we’ll be in Honduras together.

RG: All right. And then, here is Jose’s entire interview, unedited in Spanish, with former president Manuel Zelaya.

Translated Interview with Manuel Zelaya

José Olivares: Thank you very much. Well, to start — you have spoken publicly about the conflict in Palestine, with the war that continues today in Gaza.

There are almost 40,000 dead in Israel’s war. There are people who say it is a genocide against the Palestinians. Can you give us your opinion on how Hondurans see this conflict, and how the international community should respond to this conflict, and the massacre we are seeing in Palestine?

Manuel Zelaya: Look in Honduras, a large part of the ruling class was originally from Palestine. So you have to imagine that there is discomfort, even among the Honduran elite, about the crimes that Israel’s military invasion is causing within Palestine.

We consider, and Xiomara herself has said this in international forums, that it is truly an unprecedented fact in the 21st century, it is incredible that, in the eyes of the world, without respecting international law, by violating all treaties and all concepts about peace and coexistence between nations and about respecting the United Nations’ resolutions, Israel carries out a ground invasion, with tanks with bombs with the effects of violence on the civilian population of Palestine. Because, when an army fights against an army, that is a war. But this is not a war. That is a genocide, because the extreme brutal response from Israel exceeded all limits, even of those of the laws of war.

We have strongly condemned it. We believe that Palestinian children, young people, women, the elderly, should be treated responsibly, in the way— Look, the blockade against the Gaza Strip has already exceeded the limits of the global community’s humane consciousness. It stretches decades, it is a prolonged blockade, the one at the Gaza Strip. And now with this terrible aggression, solidarity with Palestine, from different sectors and different countries, is immense.

We have condemned terrorism. We condemn terrorism of any form, because terrorism violates all types of legal rules and social agreements. However, we are not limited to only condemning terrorism. The first condemnation that the Xiomara [Castro] government made, was against the bombing that affected Israel, which caused deaths within Israel, people were killed inside Israel. That was condemned — that was the government’s first action. But then the terrible response from Israel is one that totally exceeds any limit, and has the world outraged.

Do you know who has lost a lot of prestige? The United Nations Security Council. I mean, you see the Security Council of the United Nations; it has remained simply a rhetorical representation for the interests of the powerful. They have not been able to stop this aggression. They have not been able to achieve a permanent ceasefire. They have not been able to recognize the two states, the Palestinian and the Israeli states — that was one of our main positions.

So, not only are the people of Palestine directly affected, but also our entire global conscience. It is affected by this type of aggression, and the United Nations Security Council has been terribly discredited by its inability— Well, not even to respond to the resolutions of the assembly, because there have already been more than, I think, three resolutions of the assembly to demand a ceasefire. And that’s where the collateral effects come from, because the bombing leads to displaced people, it produces orphans, it produces widows, it produces abandoned people, children who are being raised in shelters, who are in camps, who do not have enough food. There is also a humanitarian tragedy there.

And where is the world’s conscience? Where is the conscience of Europe, the conscience of civilized countries? The conscience of the American people? I have seen that they have protested, but to solve the problem — because the problem must be solved — we cannot live under the crushing boot of fascism, which, in this case, is imposed on the Palestinian people.

JO: Thank you very much, President. The U.S. elections are coming this year. Polls indicate that Trump may return to the presidency. What do you think of the upcoming elections? What do you think of what we are seeing right now, in the country with the most powerful army in the world? What do you think about what’s coming this year?

MZ: Well, we believe in the democratic system, and we believe that elections are an instrument — they are not the end-all-be-all of democracy. Democracy is the power of the people. People have the power. And the people should have a holistic vision, beyond elections. I hope the people start practicing the concept of plural, solidarity-driven, humane democracy in the United States, with whichever government is in power.

We have no preference in these elections, between the Republican Party and the Democratic Party — we believe that, in the end, they act the same. They act in the interest of Wall Street, the military industrial complex, the interest of a global elite that, through capitalism, has already taken over all the assets of wealth: the rivers, the seas, the forests, oil — the world elite manages it all through the speculative financial system. The planet’s main resources, of raw economic goods, are those that influence the United States’ government.

So, in the end, you can vote for a Democratic president. We would have wanted Bernie Sanders to be president, for example, or Noam Chomsky to be president, for example. But the people, in the U.S., organize their parties, and the parties choose their candidates.

So that is important to point out, and we would like the North American people, first, to make clear that the United States should not be an aggressor empire against other societies, regardless of who takes office. [The North American people should make clear] that the United States should not have intelligence agencies planning coups, or interfere in our countries, and that that should be clear, that we must at least respect — listen carefully — the planet, so that we all have air; to ensure that climate change does not be as aggressive as it is now.

First of all, we should agree with the United States on that. The second thing is in the concept of humanism, because people don’t ask for much. What people want is to eat. What people want is to be clothed, to quench their thirst, to have a roof over their heads, and shelter and warmth. What kind of a crime is that, for human beings? And to think that the great powers, once they solve their problems, forget about the suffering in Africa, in Latin America, and in many countries in Asia as well.

So, we must demand humanity, in the face of the world order. And the United States is co-responsible for the current world order. Therefore, we must call on them (the American people) to reflect on that.

JO: Fifteen years ago, the Honduran military launched a coup here in Honduras. Soldiers entered your bedroom. They took you, while you were in your pajamas, to a military base, then to Costa Rica.

Tell us a little about what happened in that coup d’état, how the Honduran people responded to the coup, and what has happened in these last 15 years.

MZ: Look, it’s really been 15 years, as you say, and every day, that question arises. Not only from journalists, but in my house, during our after-dinner conversations, during meals, when we go out on the street with the people. That question is a constant.

A coup d’état is violent — well, the way it was here in Honduras — because this was not a soft coup. It was a military coup d’état. The human heart hurts so much and bleeds so much, that many decades will pass, and people will continue to talk about it. For me, logically, my heart breaks talking about that topic, because there is pain, there is suffering, there is tragedy. And I never thought that in the 21st century and in Honduras, which is a neighboring country to the United States — Did you know that in an hour and fifteen minutes, you can be in Miami? — they could plan an attack to break the country’s institutions.

When you break with institutions, what you do is throw out the social contract, and return to a rule by force. Because [in a social contract], by living under institutions, humans relinquish the use of force to defend ourselves. So, with these institutions, you forfeit your right [of using force] and say: well, now you defend me, and I subject to you. But when you destroy institutions that are supposed to be the “rule of law,” when you destroy the structure of the state — which they call a coup d’état — when one of those powers falls, then the people, citizens, everyone — including business owners — are left defenseless, they are subject to whoever has the most— There’s a Sandinista expression, because “pinol” is used a lot in Nicaragua: “He with the biggest throat, swallows more pinol.” That’s what awaits when the force arrives. And brute force, eh?

Well, the history of humanity — if you study the history of humanity — the history of humanity is the history of war. And the history of war is the history of religious conflicts and of conflict for the nationhood, for land, for goods.

Now they fight for other resources: for technology, for oil, but it is the same history. A coup is a war, it is the breaking of a social contract. It is the breaking of the established order, for them [coup plotters] to prevail. And you see in Honduras who prevailed: the elite, that already existed, became organized. And it was organized into a mafia. They became gangsters. They destroyed the state’s finances. They created 80 government entities in different bank trusts — 80 small governments. They destroyed the single treasury account, which is a reserve. In the constitution, there is a law that no state income can go to different sources, but rather to a single treasury account, and then the state distributes from there. They made 80 unique boxes, and, paradoxically enough, 80 governments.

And those governments enriched themselves. They plundered, they stripped the country of its wealth. That was the result of the coup. Who benefited? The transnational companies, the elite. Exonerations, concessions — the rivers, the sea, forests — they have it all. So now, a progressive government has arrived, a democratic socialist government, and we have found that the elite is protected by constitutional laws, by free trade agreements. They are protected by everything.

So, we have a bourgeois state facing demands from a democratic socialist state. That’s what we have here. That is the result —the disastrous result — of a blow to the heart of the Honduran people. Shameless murderers, reactionaries, whose crimes have still gone unpunished.

Here, the coup plotters don’t even get a traffic ticket — not even a slap on the wrist. Instead, they are offered political parties as if they are a democratic option. It is so absurd: the Honduran right, which put the generals in office who carried out the coup, proclaim themselves to be a democratic alternative. Those who murdered, those who looted, are democratic alternatives — totally absurd.

But that is what I can tell you, in a few words, about the tragedy that we experienced — something that Xiomara, with her popularity, with Libre, with the resistance, reversed. But the body of the dictatorship continues to be here. It is alive. As they say, the head of the dictatorship may be gone. But his body, with death rattles, is still kicking and shooting.

JO: Thank you so much. This week, a federal court in the United States sentenced Juan Orlando Hernández to 45 years in prison. In a document that I reviewed, U.S. prosecutors stated that Juan Orlando Hernández was receiving bribes from organized crime since back in 2005. Regardless, the United States supported the Juan Orlando Hernández government.

What does this tell us about the role of the United States in Latin America, in our countries, and during this period of — as Honduran companions here call it — the “narco-dictatorship?”

MZ: History always repeats itself if conditions don’t change.

What happened, for example in ’54 with the invasion — listen to me, it was launched from here, in Honduras — to overthrow Jacobo Arbenz, because he had started an agrarian process in Guatemala? 1954. The CIA directs — those are public documents, you can see them in all the archives, on the entire internet or on Wikileaks, they are public documents.

The CIA planned a coup against Jacob Arbenz. A reformer, military man. Reformist because at that time, when that wave came — listen to me — ’54 was before the Cuban revolution. And before the Cuban revolution, before Jacobo Arbenz, a Nicaraguan military sergeant had already been protesting. Protesting against imperialism, protesting against the invasion of Nicaragua, protesting against the oppression by the system. That was Augusto Cesar Sandino. And listen closely — that was in the first half of the 20th century. There was already the example of the Bolshevik Revolution. The October revolution, of the Soviet Union, had already taken place. And there were demonstrations, rebellions, protests in all countries. It was a very dark, very terrible time that I remember that in Argentina they trained the military to apply the national security doctrine. They instigated the types of situations, that in all honesty, generated an entire process that we can’t ignore, just as we cannot ignore what has been happening in Honduras, with the repercussions that this process has had.

You told me that — in this question, there was a detail that caught my attention. What happened, what were you telling me in this question?

JO: That since 2005, U.S. prosecutors—

MZ: How did they get here? How did drug trafficking enter?

Noriega, for example, was a CIA collaborator. And then, the United States, after Noriega’s main ally, brought in 20,000, 30,000 marines, helicopters, and they overthrew the government, and tried him. He spent 20 years in a prison in Miami, then another year, a couple of years in France, and then they sent him to die in Panama. They sent him the last year of his life, just so he could die in Panama. And he was convicted of drug trafficking. Pay attention, I’m only giving you general information. But you asked me something specific.

Here in the, in the first years of this century, in the, more or less, in the second decade of the 21st century, a Honduran Air Force general shot down two unidentified planes that carried drugs. They sanctioned and fired him, precisely at the request of the United States, because they said that two infiltrated DEA agents were there. And the general was violently removed. No, not with weapons and not as an impeachment, but it was a violent action, performed through a resolution.

So, who understands them? That’s why I’m telling you — who understands these North American policies? Juan Orlando was their main ally. Not since 2005. According to these investigations by the DEA, the Hernández cartel begins in 2002, when— Look, I’m going to give you the facts.

Ricardo Maduro from the National Party won the election, following the government of Carlos Flores from the Liberal Party. And the president of Congress started a political campaign, and his congressional secretary, and his campaign coordinator, is Juan Orlando. Essentially, I am going to specify that— If Flores enters in ’97 in ’98, ’99— OK, Ricardo Maduro’s government is here. And according to the DEA, that’s where the cartel begins to form. Of course, when Juan Orlando is the congressional secretary.

That time is when I also began my political fight for the presidency, during the government of Ricardo Maduro. Then, I replaced Ricardo Maduro. I replaced him as President of the republic. And there are the reports that the DEA itself has published, where the drug traffickers say that — they have specifically said it in their statements – I don’t have to believe them, why believe them? But they have clearly stated that they financed my overthrow. And that they gave money to my adversaries to contribute to my overthrow. Because they didn’t let me finish my presidency, I had seven months left. And when the National Party takes power — they made a statement there, in that trial in New York, saying: “We will never again leave power.” And they practically swear an oath.

So, of course, perhaps what your underlying question is: A cartel was formed. Not just bribes. They formed a cartel within the state itself. But there is an interruption for the cartel: They are in government, they lose the elections, and from there they overthrow me, and then they take over again. And they remained in power for 12 years and seven months until the people, united they consciously, responsibly, placed Xiomara — a leader who emerges from the resistance — and made her president. So yes, it began a little further back than 2005. It was a process.

Today, the United States, which supported them the most — the ones who supported the execution of electoral fraud, the ones that remained silent — the State Department, never made a statement regarding human rights, against an allied government like [Juan Orlando’s]. Simply because the Honduran government supported Juan Guaidó. If this Honduran government supported Juan Guaidó — who is a spurious president; who is not a president, he emerged from the street and proclaimed himself the only president. So, the United States did not touch the government. Under this concept, Honduras did suffer a blow to its economy, to its public finances. Debt, misery, poverty, violence and, therefore, corruption, increased. How can you judge the behavior of the United States with this sentence?

I should say — he was convicted, but the sentence downplays his conviction. Because he was convicted for three crimes, and the prosecution asked for the maximum sentence for those crimes — and he was given the minimum sentence for the crimes. For me, I mean, as politicians, we are not worried about that, absolutely not at all. Because we believe that justice should be applied in our countries. We shouldn’t try to influence the American justice system, in any way. They have their own way of acting.

They recently freed General Cienfuegos, from Mexico. They arrested him, then the State Department released a statement and the prosecutor’s office withdrew the accusations and said our relationship with a brother country like Mexico is more important than capturing General Cienfuegos. So there is your general. And they returned him to them. So, what is our perspective, at these heights, as Honduras, a small country, which is not nearly the size of a small city in the United States? What is our perspective? We see that there are agreements that allow this, according to the laws of the United States, negotiations. And that is, as a politician, I said it before, we are not worried about Juan Orlando being punished. I want them to take more time away from his sentence, so that he can return to Honduras, soon, and defeat him again at the polls. Because the people no longer want that type of sickly, harsh sectarianism, of dictatorship, of repression, that has subjected Honduras to 12 years and seven months of dictatorship. The people no longer want it. So we are not worried.

And now they sentenced him to 45 years. I already said that the sooner they bring him back, the sooner the United States, itself, will realize that there is a people here, empowered by their independence and their sovereignty, who are willing to seek compromises, because we are peaceful. We do not carry out clandestine or subversive acts, nor do we use weapons, much less do we use terrorist activities. We are a peaceful people who want to defend ourselves at the polls, but we want the United States to respect us, just as we have to respect them.

JO: Thank you so much. Can we do one more? One last question?

MZ: Yes Yes.

JO: Well, this year, in 2024, Latin America is a state of many contradictions: We have several progressive presidents in Latin America — Gustavo Petro in Colombia, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, the election of Claudia Scheinbaum in Mexico — several countries with progressive leaders. But we also have the threat from the right: Javier Millei in Argentina, perhaps Trump’s return to the presidency in the United States. And, at the same time, there is also the power of multinational companies, and the threat of American imperialism.

What is your perspective, personally, about the future of Honduras, the future of Latin America? How do you see the future of our countries?

MZ: One thing is to have hope. And another thing are the challenges you have to confront, in order to not lose hope. We have faith in ourselves, in humanity. One honest person can save many others who could be destroyed. That’s biblical. When the Lord in the Bible appears to the one who asks him to destroy Sodom and Gomorrah and says:‘Look, these cities are rotten, there is corruption here, there is selfishness, vanity; you must destroy Sodom and Gomorrah.

And is there anyone honest?’ The man asks him. ‘Is there anyone?

Yes, there is one.

Well, that’s why the others should be saved. That’s why I shouldn’t destroy it, then.

There are honest people in the world — there are honest people, who have hope to find solutions.

We are not concerned about the coming and going of history, which swings to the right then left. People react based to the type of government, or circumstances, that afflict them. When progressive parties govern and continue to maintain the neoliberal model, then people go against the progressive party and get rid of them at the polls and remove them.

Now, when you have parties, mind you, from the right, as in this case — you are mentioning to me the various right-wing phenomena that exist in Europe and here; the emergence of fascism is evident. But those parties come to power, and what do they do? Instead of giving the people what belongs to the people, instead of respecting Lincoln’s great slogan that democracy should prevail on this earth, what does the right do? They worsen their extreme measures of exploitation and cruelty of the people, of the working class.

Then the people take them down again. So it is a dialectical cycle, as Hegel said; there is the idea that contradicts the other idea [thesis and antithesis]. And, as José Martí said: “the trenches of ideas are stronger than the trenches of weapons.” So, we don’t have to be afraid of what is happening. Those of us who believe that we must defend justice, and the integrity of people — to not let them die, and to alleviate suffering, give them the greatest degree of happiness — we believe in that. Every day we are stronger, because our martyrs fuel our forces. If someone is able to sacrifice themselves and give their life, then why can’t I do it? We are only in the world temporarily.

Other generations will raise those flags, and they will do it with closed fists; a sign that their collective consciousness will strengthen. Life is an accident. You must give it meaning, and the meaning has to nourish you; you don’t have to serve it. Otherwise what use would it be, then? That is, you have to think that we are beings with emotions, we are not stones. Nature and the creator of the universe managed to form this entity of cells that suffers, that cries, that laughs, that enjoys, that can enjoy music, enjoy the chirping of a bird, the sound of the waves — this state of being, we must preserve it. And this being, of course, there are two perspectives: The first is that we must preserve the human being and humanity. And for that, we have to develop science and technology. We agree that’s the way to preserve it. But not by creating an apocalyptic system, like libertarian neoliberalism, that they are sustaining in this moment. This is an apocalyptic system. That is not going to solve humanity’s problems.

We need, above all, consciousness and to agree on the value of life, not the value of material items. We believe there is a significant development in the ideas that have been developed this past century. The 20th century was the century of enlightenment. But in the 21st century, in the century of communication through the internet, consciousness is spreading to the last corner of the earth, about what is happening. Today we are the global village, which was spoken of at the end of the century. Today, yes, we feel that unity is becoming stronger. So I have faith in that.

Look, I have always placed a lot of trust in people’s common sense. You may have an illiterate person – unable to read or write. But he will have a greater sense of justice, than the most intellectually developed person. He has more of a sense of power. Power is a human instinct. Power is like food. People can be peasants and know what power is for, and how power is used. That is something in a person’s mind: Power, will, justice and the most sacred thing, freedom.

But it is not the freedom of Mike Tyson, and I admire Mike Tyson — it is not the freedom of a boxer like Mike Tyson, who gets in the ring and challenges you, and you know he is going to kill you with one punch. That is not the type of freedom I am talking about, “that we are all equal,” no. We are all equal according to our capabilities and according to our needs. To create fair governments in a better world, that is still possible. We have not lost our faith. And I think that’s what keeps us standing.

JO: President Zelaya, thank you very much for your time.

MZ: Well, same, same. Thank you for coming here. Thank you so much.

Credits

RG: That was Manuel Zelaya, and that’s our show.

Deconstructed is a production of Drop Site. This program was supported by a grant from The Intercept. This episode was produced by Laura Flynn and José Olivares. The show is mixed by William Stanton. This episode was transcribed by Leonardo Faierman. Our theme music was composed by Bart Warshaw. And I’m Ryan Grim, cofounder of Drop Site.

If you haven’t already, please subscribe to Deconstructed wherever you listen to podcasts, and please leave us a rating and a review, it helps people find the show. Also, check out our other podcast, Intercepted.

Thanks for listening and I’ll see you soon.

Latest Stories

AIPAC Millions Take Down Second Squad Member Cori Bush

Bush was early calling for a ceasefire in Israel's war on Gaza. Then AIPAC came after her with millions of dollars.

The U.S. Has Dozens of Secret Bases Across the Middle East. They Keep Getting Attacked.

An Intercept investigation found 63 U.S. bases, garrisons, and shared facilities in the region. U.S. troops are “sitting ducks,” according to one expert.

What Tim Walz Could Mean For Kamala Harris’s Stance on Gaza and Israel

Walz allows for Harris to “turn a corner” in her policy on the war in Gaza, said James Zogby, president of Arab American Institute.